by Larry Chowning –

The first African-American graduate of Christchurch School (CCS), founded in 1921, was Wayne Edward Toney of Topping who received his Seahorse diploma in 1973.

Toney was recognized at a 2008 Christchurch Hall of Fame ceremony with a plaque that reads “Christchurch School is pleased to honor as an Alumnus of Distinction Wayne Toney — In recognition of his pioneering role as the school’s first Black-American student graduating on June 2, 1973 and thereby leading by his effort and example a change that has forever enriched Christchurch School.”

The 1960s and 70s were a social and racial transition period in Virginia education. Public and private all-white schools in the state were either being forced or strongly encouraged to integrate.

Virginia’s “separate but equal” laws going back to post-reconstruction Jim Crow laws that legally forced segregation of whites and blacks in every aspect of life — including education — were falling apart as Supreme Court rulings, one by one, found the laws unconstitutional.

Middlesex County Public Schools (MCPS) were federally forced to integrate under a “freedom of choice” plan in 1963 and by 1969 MCPS schools were totally integrated. By then, Christchurch Church School, an Episcopal Diocese of Virginia supported private secondary school for boys in the county, was feeling pressure to begin integration. The first Black to enroll in the school was Otis “Lanny” Stanley in 1971, who entered as a sophomore.

Wayne Toney joined Stanley at CCS in 1972 as a rising senior. He was an ideal choice to become a trailblazer in the first days of integration at CCS. Wayne’s education had been confined to private Catholic integrated schools in Richmond bringing some experience to an integrated school setting.

He also had strong ties to Middlesex County and CCS. His grandfather was none other than Dr. Marcellus E. Toney Sr., the first African-American doctor to practice in Middlesex County. Dr. Toney had moved from Baltimore to Middlesex in 1927 and established a medical practice near Cooks Corner.

Wayne’s father, Dr. M.E. Toney Jr., graduated from Middlesex County Public Schools and went on to earn a doctoral degree and worked in research at Virginia Union University. His father and mother, Louise, raised Wayne in Richmond.

“I had attended Catholic schools all my life and went to Benedictine, an all-white military day school, in the ninth and tenth grades,” said Wayne. “I had a bad experience at Benedictine and my parents enrolled me in Thomas Jefferson (TJ) High School (a public school in Richmond) for my junior year.”

His experience at TJ was not bad but Wayne made an unforgivable mistake in the Toney family. “I got a D in Algebra for the year,” said Wayne. “That was unacceptable to my parents and they told me, ‘you are going to Christchurch!’ ”

Joe Cameron

“I really never wanted to go to an all-white boys school but I had no choice in the matter,” he said. “The only positive thing about enrolling in the school was that Head Chef Joe Cameron was my uncle.

“When Uncle Joe heard that I was enrolled,” he said, ‘Wayne Nonney (that’s what he called me) don’t you worry about anything. I will take care of you.’ ”

“I learned quickly that when Uncle Joe spoke, everyone listened!” Wayne said. When issues arose over sitting arrangements for Wayne in the cafeteria, Joe Cameron got everyone’s attention. “No one wanted me to sit at their table and Uncle Joe asked me why I was not sitting with the other boys. I told him, they didn’t want me to.”

“He came out of the kitchen and announced to the student body, ‘Wayne Toney is my nephew and I want him to be treated with respect. Now, wherever he wants to sit he is going to sit and if anyone has a problem with that, all this good food that I cook for you will end today and everyone will be served cream of wheat until he gets the seat he wants.’

“After that speech, I never had to look for a seat at the table again,” said Wayne.

Benefit of Christchurch

“At Christchurch the teachers and classmates taught me different aspects of life,” said Wayne. “Jean Jones (English teacher) taught me a new expanded vocabulary that was necessary to be understood by people who did not look like me.

“Catherine Seaton taught me how to speak in front of crowds and how to keep their attention,” he said. “She said life is like a play. We all have different roles and we are all actors. She emphasized that we must learn to play the roles we want to play in life. I’ve carried that message with me from Ms. Seaton my entire life.

“Thanks to Casey McCue (a student), I learned to play drums at Christchurch,” said Wayne. “This led to me playing in jazz and funk bands later in life,” Wayne said. McCue had his own band and encouraged Wayne to learn to play drums.

“One point I’d like to make was although there was prejudice and adversity towards me at Christchurch, I felt a sense of unity being at the school,” said Wayne. “If you were a Seahorse, we all stood together and if you messed with one of us, you messed with all of us.”

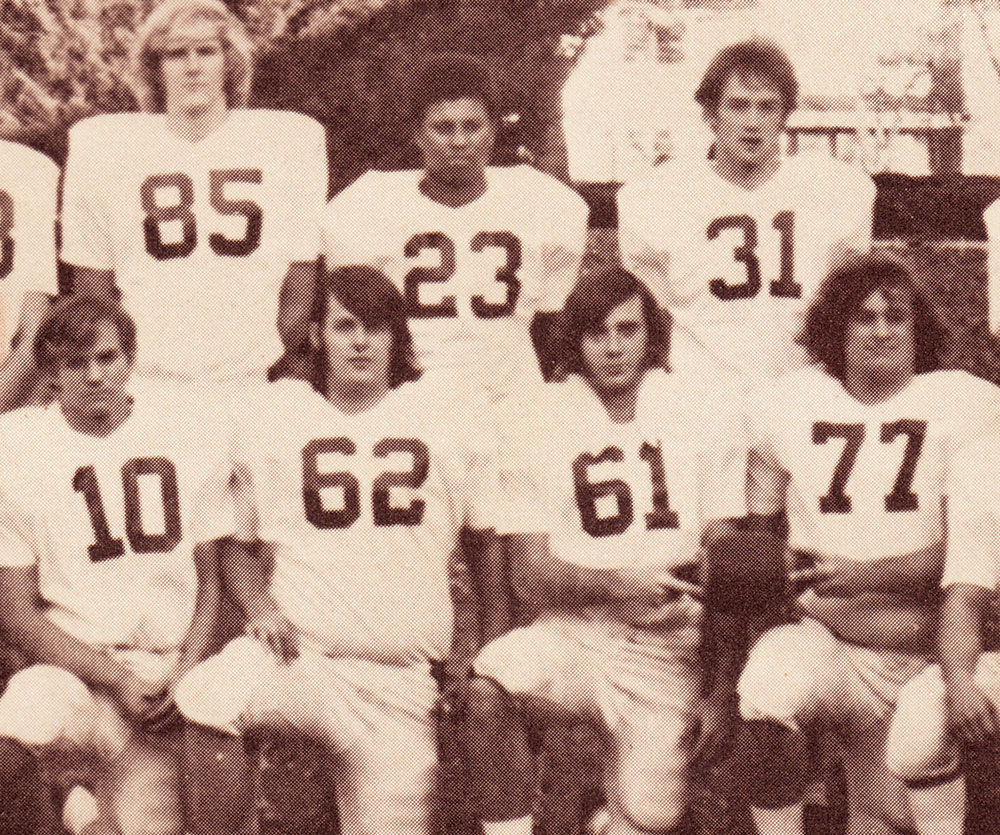

This was evident on the day Christchurch lost 68-14 in football to Wayne’s old school Benedictine. “I played fullback on the team . . . and was not the feature back. I had not gotten to carry the ball the whole season. It was late in the game and we were behind 68-7. Our offense drove the ball down to the five yard line.

“Coach (Albert) McCue knew what a hard time I had had at Benedictine. He told the team that he wanted me to carry the ball and he told the team ‘make sure Wayne scores!’

“When we lined up, I got the ball and my roommate Chuck Adcock made the block that sent me into the end zone. I scored my first and only touchdown at Christchurch. Although we lost 68-14 my teammates at Christchurch and former classmates at Benedictine were all jumping up and down celebrating with me.

At that time there was no Black, no white, no Republican, no Democrat, just a bunch of young men celebrating my touchdown. You don’t ever forget those kind of things.”

Other good memories

“It was a completely different time back in the 1970s. It was an era of stereotype, prejudice and lack of understanding of people who did not look like you,” said Wayne.

“My time at Christchurch helped me to educate all of my classmates, that I was just like them,” he said. “For example, my classmates believed the myth that all Black people loved watermelon.

“So, it was shocking to them when watermelon was served in the dining room and I would not eat it,” said Wayne. “They tried to get me to eat it but I wouldn’t. They realized that Wayne really did not like watermelon and neither do all Black people.”

Another myth was that all Black men wanted to drive Cadillacs. “Well, in 1972 when I was at summer school John Dickey (a student) had a 1967 Corvette convertible with a 427 big block Chevy engine,” said Wayne.

“My favorite car was a 1962 Corvette and in general I loved Corvettes. So I’d go out in the parking lot and just stare at his car. One day, John asked me why I was staring at his car and I told him that I liked the… Corvette and asked him if his car really had a 427 with a big block.”

Dickey was impressed that Wayne knew that his car had a 427 big block and that he didn’t like Cadillacs. The two went on to become lifelong friends, both graduating from James Madison University (JMU) and shared together their love of car racing on the Mid-Atlantic Drag Racing Circuit.

Bad memories

A bad memory Wayne carries with him from Christchurch to this day was when his senior picture was not included in the 1973 Tides Christchurch yearbook. “There are only a few events in life that you want documented,” said Wayne. “One is when you graduate from high school. The school spoiled a major memory of mine when there was no picture of me in the senior section of the Tides. You cannot imagine the hurt, anguish and disappointment I felt and have felt ever since 1973.

“The school understands my disappointment and I do appreciate that they honored me as an alumnus of distinction in 2008 at the Hall of Fame ceremony, but I will never forget my disappointment when I got my annual and my photo was not there.”

Wayne also felt his presence at CCS was tolerated but not always appreciated. He felt his race required that he work harder to make the grade and athletic teams. He recalls he was a constant bench rider on the CCS basketball team until he had an opportunity to go one-on-one with the coach, which resulted in being placed in the starting lineup.

“I felt at times it was alright to be Black on the football team with a helmet covering my face,” he said. “When it came to basketball, I felt I was on the bench because I was Black in a very visible sport.”

“When the coach played one-on-one with me and saw what I could do, to his credit, I got moved into the starting lineup,” he said.

Life after Christchurch

After leaving Christchurch, Wayne went to the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut and used his skills on the drums to play for jazz and funk bands. He later transferred to JMU and graduated in 1977 with a degree in Mass Communication.

While racing cars on weekends, Wayne taught seventh and eighth grade history at an east end Richmond middle school from 1981-1985. After leaving teaching, he opened an auto repair business in Richmond, “Toney’s Mobile Tune” in 1985. He moved to New Jersey in 1995 and opened Dr. Toney’s Auto Clinic.

The impetus behind his auto businesses came from his passion to race cars. He established WET Racing (WET stands for Wayne E. Toney), built his own race car engines and was active on the Mid-Atlantic drag racing circuit for almost 20 years. One of Wayne’s great racing moments came with his Christchurch buddy John Dickey when the two in 1978 celebrated together in the winners circle after winning their race car classes at the Richmond Dragway in Sandston. “It all started at Christchurch for us and John has been one of my best lifelong friends,” he said. Dickey, now retired, went on to own and operate Advance Engine Design in Richmond, a firm that builds race car carburetors.

A racing injury suffered in 2004 and his mother’s bout with dementia prompted Wayne to return to the family’s Beverley Beach home in Topping where he lives today.

“I would never trade my experience at Christchurch for anything in this world,” said Wayne. “It has made me the man that I am and for that I will always be grateful.

“Sometimes in life all you have are memories to keep you company,” he said. “Go out in life and make some lasting memories with someone who does not look like you. For that life will become priceless and you will be forever grateful. We are all Americans! Remember that!”

Since moving to Topping, Wayne looked after his mother and after she died has been struggling with his own health issues. “I would like to take this time to thank members of the community who have shown kindness, caring and support to me through these times of extreme loneliness, and uncertainty caused by this Pandemic. They are Ralph and Sharon Pollard, Dr. Ken and Terri Cleveland, members of Clarksbury United Methodist Church, Philip Roye, Geni Powell and Amanda Horsley at the bank and my adopted family Col. Gary and Lynn Richardson. Thank you all for caring.”

(Writer’s note: Wayne Edward Toney is a pioneer and important figure in Middlesex County history who as the first Black graduate of CCS paved the way for generations of African and white Americans to be apart of integrated education in Virginia. I thank him for sharing his story.)